Happy Native American Heritage Day! In honor of the occasion, we asked an indigenous paranormal enthusiast and business owner, Jennifer Pictou of Bar Harbor Ghosts Tours if she’d like to share our platform and tell a ghost story about her region. Jennifer is a member of the Mi’kmaq Nation, the owner of Bar Harbor Ghost Tours and a Storyteller, Folklorist & Artist.

I love a good curse. I mean, who doesn’t? Everyone has heard of one, in fact curses are the basis of our most popularized fairy tales. Usually given by a wicked witch, the curse is placed upon a specific victim and for a specific amount of time or until certain actions are performed by others. Only after the stated requirements have been fulfilled is the magic finished unless it can be broken early by other, magical means. It gives us hope to think there may be a way out of a curse but hey, that’s only if we are unlucky enough to be on the receiving end of one, right? But wait…what if there was a curse that didn’t have a particular person as a victim and had no end? The Saco River Curse is one such malediction; a dangerous mystery that still lingers in whispered conversations by Mainers, reminding us to not take our fragile mortal state for granted lest it be swept away in an instant.

To find one version of the Saco River Curse is impossible for like the river itself the legend takes many twists and turns, not appearing the same to anyone who looks at it no matter what the angle or era. The approximately 125 mile river has been described in human psychological terms such as schizophrenic, lazy, playful, charming and gracious, as well as cruel and vengeful by the Portland Press Herald. However, as the legend itself speaks of unusual magic, retribution, and unassailable grief so does the longevity of the curse speak to deeply rooted social anxieties and cultural misconceptions towards Indigenous Peoples in New England. Over three hundred years after the curse began it is still alive and well, having survived since the 17th Century to provide each generation a combination of a moral tale, an example of Indigenous cultural resistance, and an anchor to a specific place in space and time.

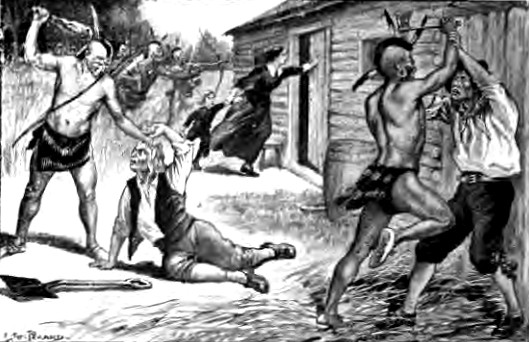

During the latter part of the 17th Century in the settlement of Saco Falls there was a leader of the Sokokis (Saco) Tribe named Squando. He was considered a friendly Native with the English, a reformed drinker, and a converted Christian as well as a husband and father. One day Squando’s wife was paddling her canoe across the Saco River with the baby resting peacefully inside it (in almost every version of the story his baby is male). Two English sailors saw her and began bantering among themselves about how supposedly Native babies could swim at birth just like all young animals. In order to test their wager, they accosted Squando’s wife, took the baby and promptly dropped him into the churning and dangerous river. Squando’s wife dove into the water after the baby and brought it to the surface but he died before morning despite all efforts to save him. Squando, in a fit of rage against his former English friends, is said to have cursed the river to take the lives of three white men each year.

The true history of Squando’s odium toward the English however, was evidenced by his action to join in King Philip’s War. From 1675 to 1676 he led many raids on white settlements, resulting in the English settlers fleeing from the area of Saco Falls to Winter Harbor. History indicates the first time Squando is noted in official English records is at the signing of the Cocheco Peace Treaty between the English and Natives on July 3, 1676. However, the curse itself was first recorded by Seba Smith in 1846 in Dew Drops of the Nineteenth Century.

At its essence, a curse is a spell. According to Puritan beliefs at the time, all Native people were witches and/or bewitched therefore, could bring great calamity upon the settlers through magical means. The fact that Squando was known to not just be a leader but a healer also gave validity and greater power to the belief in his curse.

The curse itself has been handed down through the lens of Colonial Settlers. By that I mean it is problematic to view it through assumptions we take for granted as contemporary everyday experiences. The following list is based on several key assumptions:

- It is based in the Gregorian calendar and not the thirteen-moon yearly cycle of local Indigenous peoples that would overlap and distort a timeline.

- A space or feature of the land is viewed to be cursed instead of a localized person or family.

- It is not given a specified period of time other than the annual cycle thus there is no end.

These assumptions make this specific malediction different than many other fabled examples, but why? Is it simply due to the inherent nature of Indigenous curses to be so vague or is there an underlying reality that makes it so strong that we delude ourselves in labeling it a simple curse so we can feel better about the unknown parameters?

The most problematic of all unknown parameters is time. There has not been given an eye witness account of the events that unfolded surrounding the curse therefore wording, actions, ritual, etc. is missing. Since so much time passed between the events and the telling of the curse, we can only assume what cursing a river meant based on the popular culture stories we grew up with in our various contemporary societies.

So where does this leave us? I’d like to posit my own theory.

The Saco River Curse has had a huge effect on the people in the Saco/Biddeford area. Local newspaper accounts throughout history have counted and claimed lives lost due to its ongoing killing spree and locals remember their mothers not letting them swim in the river until three people had died in it every year. It seems everyone knows about the story and those who don’t, ask for it in whispers. From the top of Maine to the bottom, it is known as a mysterious and awful spell with greedy fingers always searching for more victims. The longevity of the curse has grown roots and worked its way into the very fabric of the cultural landscape.

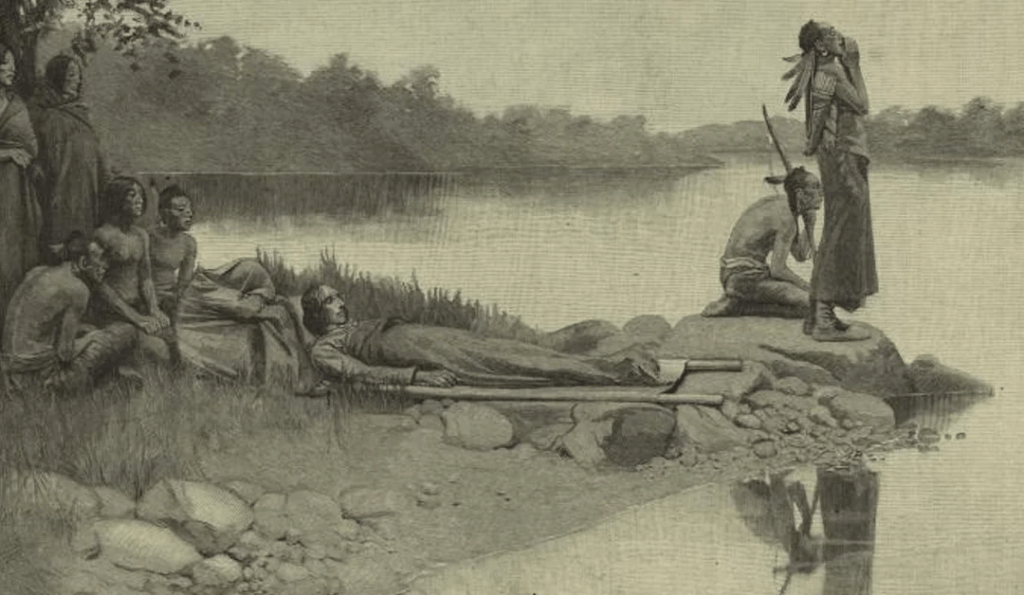

In reality, Squando would not have given up his cultural beliefs in a spiritual world beyond the settlers’ Christianity. A world where once humans, plants, and animals could talk to one another and shapeshifting spirits were the norm; a world where spirits were imbued in the rocks, trees, water, and air. Not forgetting who he was and his deep cultural heritage, it stands to reason that he would not have cursed the river (in the traditional English sense) but instead would have made an offering and asked for assistance of the water spirits in his quest for justice against the two sailors who were responsible for his child’s death. After all, the water spirits would have borne witness to the tragic events and the injustices that followed. Once ceremony was completed and the water spirits were given a focus, they would not have been controlled by Squando but acted in their own agency to carry out the requested retribution. A time constraint would not have been needed, giving the curse an outward appearance of being timeless. Squando would most likely have believed in the cyclical nature of seasons and annual time, and as spirits act in their own time and at their own pace would not have needed an end date or “until such time as xyz is complete.” This timeless nature helps account for the many people over the last 300+ years who have entered the river only to come out alive and claimed to have beaten the curse. Simply put, the spirits weren’t interested in them.

It is the water spirits that really make this curse less of a curse and more of a paranormal act of vengeance year after year and therefore even more terrifying. Knowing there are spirits actively hunting among the thousands of swimmers, boaters, fishermen, etc. who play on the Saco River annually makes each and every encounter a test of one’s spirit where passing and failing literally means life or death. It is an immortal haunting by spirits seeking vengeance, having been set upon a path of taking lives, as they see fit, by a grieving father.

As of 2022 the Saco River is slated for a memorial to Squando’s family.

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

Mi’kmaq Nation Owner, Bar Harbor Ghost Tours Storyteller, Folklorist, Artist